I have an essay out in a new anthology called Women Talk Money, edited by Rebecca Walker. I’ve had a giant intellectual crush on Rebecca since I heard her speak in Sydney several years ago, so I was pretty excited when she invited me to contribute something (and, wow, is the list of other contributors a total dream). I wrote the essay back in 2019 and then sort of forgot about it while the slow wheels of the publishing industry cranked on. At the time, before the pandemic changed so many things about our lives, I had a lot that I wanted to say about money. I hoped that writing the essay would help me make sense of my own tangled feelings. Now, looking back on this essay that is both old and new, I can see through the sentences to the writer behind them. She is trying to be transparent and open about money, but she is squirming.

The essay is about my book deal. My agent called it “the kind of money that could change your life” and it did change my life. But it also completely upended my sense of who I was. The dollar amount on that contract was far out of proportion to how I thought about myself and my career. I was equally thrilled and embarrassed and I wanted everyone and no one to know about it.

I tell that story in the essay so I won’t tell it here. But I will say that the experience helped me think more critically about the role of money in our lives, particularly one of the most basic assumptions of capitalism: the idea that money is earned and therefore deserved. It's not that I’d never questioned this before, but it had always been more of an abstract thought exercise. When I got that advance, I knew I did not deserve such a hefty slice of the pie any more than I deserved earning so much less in all the years that preceded it.

Pointing out that capitalism, with its emphasis on the accumulation of individual wealth, is a lonely economic system isn’t exactly a revelation. Adam Smith argued that the pursuit of individual interests would ultimately benefit everyone, writing, “It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest. We address ourselves, not to their humanity but to their self-love, and never talk to them of our own necessities but of their advantages.” So, in other words, for the free market to succeed we should each pursue our own ends while never acknowledging our needs. Can I just say that I hate this idea? I suspect that if we believed this pursuit of individual interests distributed resources fairly—that we got what we deserved and deserve what we’ve got—it wouldn’t be so difficult to talk about money. But talking about money comes easily to almost no one. (For example, I hoped adding “baby” to the title of this newsletter might make me sound more confident. Is it working?)

In the literary world no one talks about money, though every writer I know is obsessed with it. Or every writer I know is obsessed with the thing money can buy: time to write. Publishing can be a brutal industry. But then any creative life is a poor fit for capitalism. In our culture writing is both a passion that you should pursue for little or no pay and it is a career where the only legitimate version of success is the one where you make a living from your art. Because we want both things to be true, most of us never acknowledge how money comes to bear on our writing lives. Instead, we’re all scrolling through Instagram sure that everyone else resolved this contradiction years ago and wondering where we went wrong. Or this is how it’s always felt to me. It probably doesn’t help that book advances are usually spoken about in code while the average author’s income is steadily declining.

In my essay, I wrote that silence around money perpetuated inequities. So when the Publishing Paid Me hashtag started circulating as a way to expose racial disparities in the publishing industry, it felt like an opportunity to stop being silent. (I guess this is one thing I like about essay writing: it forces me to really consider where I stand on something and then to be accountable to those ideas.) I saw that Roxane Gay had used the hashtag to share the advances of her first few books. I was surprised by some of the numbers, so, without thinking too much about it, I retweeted her and added, “I, a totally unknown white woman with one viral article, got an advance that was more than double what @rgay got for her highest advance. #publishingpaidme $400,000 for How to Fall in Love with Anyone.” I went on to say a bit about what I did with that money and what it made possible for me as a person and a writer.

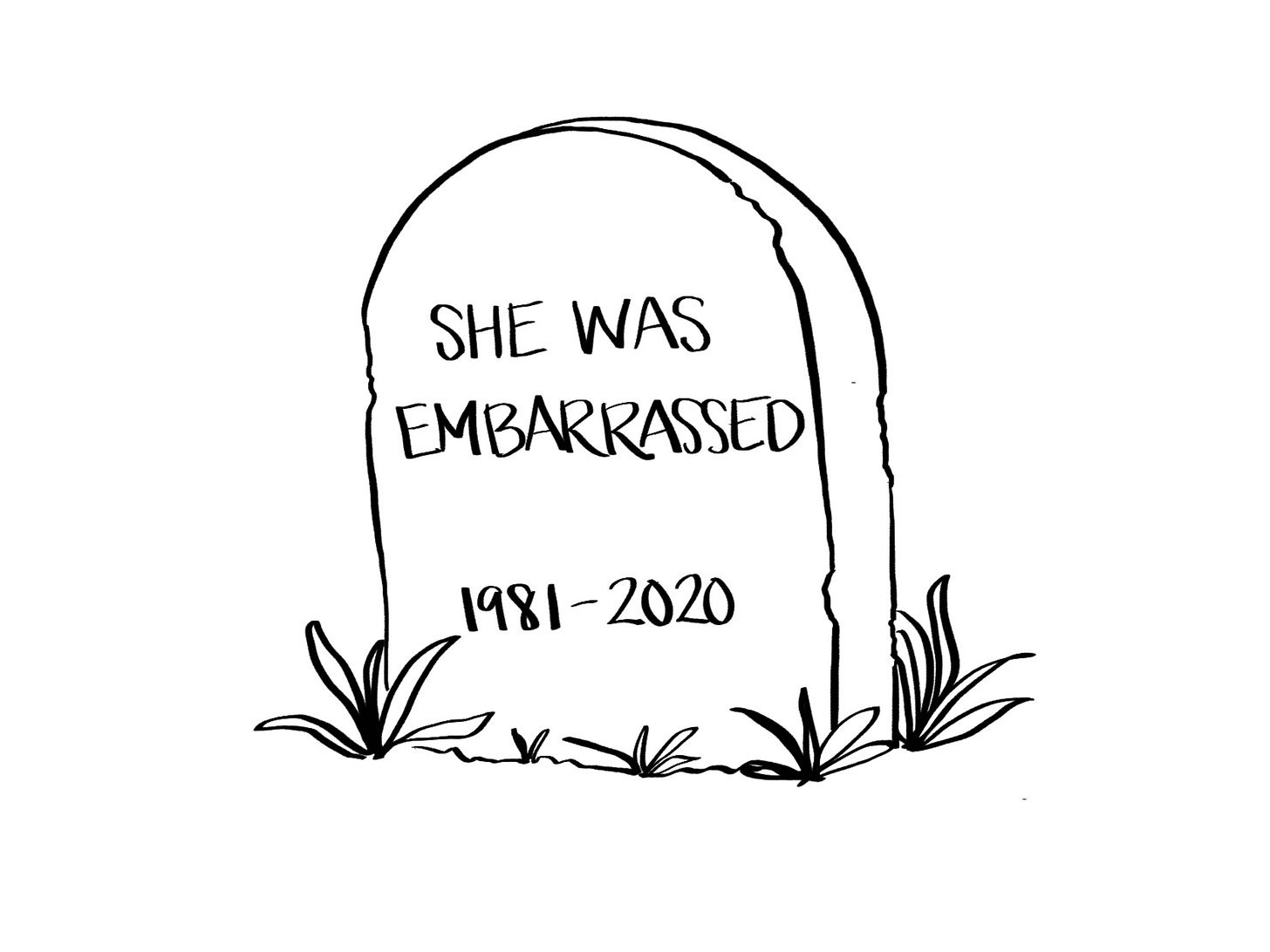

It seemed like the right thing to do, but I felt my skin catch fire about thirty seconds after I hit send. I wanted to die. I wanted to die when the responses started coming in. I wanted to die when Roxane Gay retweeted it. And I wanted to die when I saw my tweet in a New York Times piece on the overwhelming whiteness of the publishing industry a few weeks later. I want to die a little bit now as I’m typing this. I still think it was the right thing to do, though I sometimes wish I’d phrased it differently, in a way that better acknowledged some of the forces at play behind the advance. (Like, it wasn’t quite accurate to call myself “totally unknown” or to understate the readership of that viral article.)

On Twitter, the responses came in three forms, all of which were humiliating in their own way. A few people praised me for my willingness to be honest. That was nice but it also reminded me that being honest about your good fortune is not the same thing as, say, redistributing that fortune to those who need it more than you—something I was still trying to get comfortable with after years of precarity. A few people suggested that I was just bragging and clearly thought I was better than Roxane Gay, which made me wonder if in fact some part of me was bragging and actually enjoyed the attention and I just didn’t quite realize it. (I did not.) The third response was basically: I don’t know her—a lot of people trying to figure out why they hadn’t heard of me, which at least made me laugh. It is still, by far, the most popular thing I’ve ever tweeted. Being the literal face of white privilege in the New York Times still makes me want to die, but, as of this publication, I’m not dead. (Also, you should absolutely read that article if you’re remotely curious about race and publishing.)

The truth is that the advance had made me feel special, just as I’d always hoped to be. I hate admitting this, even though I know it’s entirely predictable. The figure on that contract suggested that maybe I was more deserving than all the other hardworking writers I knew, and part of me really wanted this to be true. I let this possibility live for a while, safe and secret in the harbor of my own mind. But I couldn’t sustain it; there was too much evidence to the contrary, too many talented writers making too little money.

But talking about it was awful. I was afraid that everyone would see me for exactly who I was: someone who had been overpaid, someone who was clinging to the coattails of her privilege, someone who was definitively not special. Even worse, they would see how much I wanted to be special and how deeply ordinary I was instead. For most of my life, I believed that nothing was more humiliating than the gap between who you wanted to be and who you really were. (It’s the moment in every 90s teen movie when the dorky freshman girl actually kind of thinks she has a chance with the dreamy senior guy, even as we all know she does not.)

I suspect that if my book had gone on to become a bestseller, which it did not (unless you count a very specific category on Amazon), I would’ve found it easier to believe in my own deservingness. And in a way, I’m glad it was not a wild success, because it allowed me to consider a more interesting possibility: no books are more deserving than others, no authors more worthy of financial reward.

In her introduction to the anthology, Rebecca writes that we live within an economic system “designed to keep us all separate, in our respective places.” I think this is true: so much of the loneliness in our modern lives is dictated by a deeply unjust and unsustainable economic system and all the ugly ideas packed in its bags. Even though I had been rewarded by that system when so many are not, that feeling of separateness wore on me. I felt this acutely in the classroom, when students asked about how to make a living from their work. I knew it was possible to pay the bills writing books, but I knew, too, that it was increasingly rare. Financial success relied more on luck and timing than it did on talent or hustle. Not acknowledging this felt fraudulent. I didn’t want to be complicit in the mythology of the successful writer.

I'm still figuring out what a less lonely version of life in our neoliberal capitalist culture might look like for me—and I hope to write more about it here. For a while, I had a practice (a very unstructured practice) of regularly giving directly to folks who needed it in hopes that I might start thinking of money as a resource that moved through my life, instead of as something to be hoarded for an uncertain future. But of course the arrival of two new humans in our home has complicated things.

Rebecca Walker says that her own experience talking about money with the women in her life set her free: “Not free from bad decisions or patriarchal, white supremacist capitalism, but free from thinking that its machinations and mutilations, its structurally maintained inequality and callous disregard for life, the earth, the future, was somehow my fault, my crime, my cross to bear. Free from thinking I was alone in it, this story of money and how it shaped my life. I was not.”

Talking about money is uncomfortable but, for me at least, not talking about it is worse. I don’t want to live a life where one’s social value is determined by how much you have and how little you need. Talking openly about money doesn’t fix the vast inequities of capitalism, but I am trying to think of it as a practice that, for all its attendant awkwardness, turns my attention away from Smith’s vision of self-interest and toward the world around me.

Talking about money is uncomfortable! Yes, even taboo or, at the least, tacky. Yet I’ve learned many valuable life lessons talking with friends and even strangers about money. Find a path to a discussion. It’s worth the uneasiness.

Congrats on the new book, even more excited to read it now.